Dunning-Kruger-Power Effect

An erudite and a megalomaniac walk into a bar

Dunning-Kruger

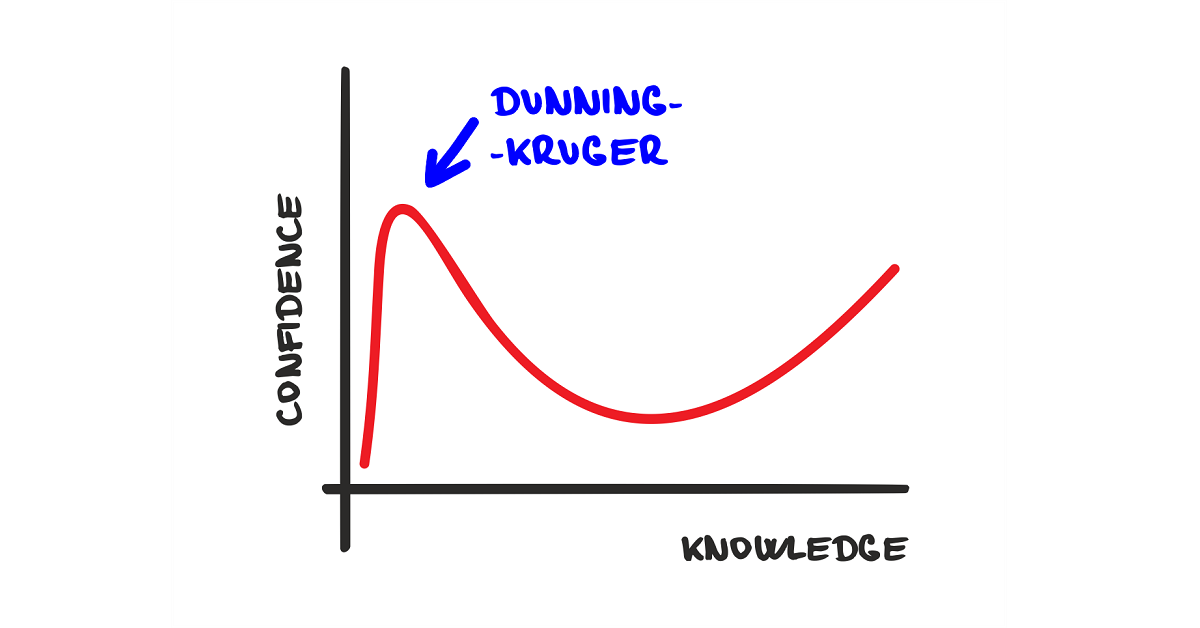

The Dunning-Kruger effect is probably familiar to anyone who studies psychology or has stumbled upon it on the internet. It is a useful phenomenon to be aware of, but there is more to it than meets the eye. To start, let’s explore what it is with a graph:

The first thing to note is this graph exists for any given domain of knowledge. Let’s take one example: climate change. The x-axis is a measure of how much knowledge one has on the topic of climate change. On the y-axis is a measure of confidence (also sometimes conviction), roughly indicating how sure one is of one’s views on climate change. What happens is with a very minor amount of effort invested in learning about climate change (accruing knowledge, or moving to the right on the x-axis), a disproportionately massive gain in one’s confidence (moving up the y-axis) occurs. The resulting maximized confidence (or conviction) in a domain of knowledge is piety, and as you can see from the graph, confidence is maximized when knowledge is relatively low. Mount Piety as I call it, is known as the Dunning-Kruger effect, and is this point where one’s views are most unflappable despite being relatively unknowledgeable.

Piety refers to a religious-like devotion to a belief, made stable (i.e., incontrovertible) by a commitment to ignoring additional evidence. In other words, there is an inertia preventing one from pursuing further knowledge once they have summited Mount Piety. But what makes someone pious? What prevents an individual from relinquishing confidence in pursuit of additional knowledge? Many have argued that this is a natural feature of being human - the desire to be right and the fear of exposing all that you don’t know. I don’t buy that for one second. To me it is clear that there is a force preventing people from doubting their convictions. That force is power.

Knowledge is power. Or is it?

Here is an updated figure, hand drawn by yours truly, with a subtle but important modification:

What may be thought of as a relationship between knowledge and confidence is actually something else. Individuals end up on Mount Piety because power drives individuals to gain knowledge, not because erudition does (i.e., knowledge for knowledge’s sake). In fact, if one is motivated by erudition, this plot looks very different. An erudite might have a momentary rise in confidence early on, but they will see it for what it is: a trap. Unflinchingly, the erudite will press on, welcoming the Valley of Vulnerability with open arms, climbing the Hill of Mediocrity with Sisyphean tenacity, and will end up on Humble Plateau that conspicuously never reaches the same elevation as Mount Piety. Most importantly, the erudite may stumble into some power at the end of this journey, but power is not the justification for it. The megalomaniac on the other hand is motivated by power.

What is power? Power is possessing the legitimacy to influence others, and most people want it. If you don’t believe me, consider that a 2017 study showed over 50% of 6-17 year olds want to be Youtubers or Bloggers when they grow up. Researchers are tripping over themselves trying to explain why so many kids want these jobs, when the explanation is really quite simple - people want to be in positions of influence. People, even children, want power.

[Like many things in modern society, no longer do people want to earn the benefits of the system honestly, they want to game the system to access the benefits directly (a process I call the gameification of everything). Instead of pursuing careers that come with influence as a deserved side-effect, becoming an influencer is the new posh.]

The cynical reality is that most people do not acquire knowledge to become more erudite for erudite’s sake; people acquire knowledge to gain power. Of course, people don’t realize they are motivated by the power to influence others. In fact, most people will provide a perfectly noble explanation for their pursuit of knowledge. After all, informing oneself about the dangers of climate change is a moral responsibility, innit? Self-deception and false noble motives aside, people acquire knowledge to gain power, and once even the tiniest modicum of power has been gained, it is nearly impossible to get them to relinquish it.

The point that the Dunning-Kruger effect misses, is that power-driven pursuit of knowledge makes it nearly impossible to descend Mount Piety, because gaining further knowledge means relinquishing power. Individuals atop Mount Piety would perceive any movement towards further accruing knowledge as a dangerous step towards losing power. Fortunately for the megalomaniacs, there is a solution to appear increasingly knowledgable, without ever having to descend into the Valley of Vulnerability: information.

Information differs from knowledge in an important way: it does not change the relational structure of understanding, but reinforces existing structures of integration. Knowledge is the ability to parse information and integrate disparate sources of information into a cohesive structure. Information is the data used to support the relational nature of knowledge. What accruing information does, in effect, is allow individuals to build a fortress around their existing knowledge, without incorporating new knowledge into their cognition. It can be difficult to differentiate someone who is rich in knowledge, from someone who is rich in information, from someone who successfully integrates both.

If you need an example to clarify this point, consider the wealth of data available on the topic of atmospheric CO2 levels. An erudite would be incentivized to learn that prehistoric CO2 levels were once much higher than they are today (1,2,3), higher CO2 is associated with higher, not lower, biodiversity (1,2), that atmospheric CO2 does not correlate with global temperature (1), and that even if the Earth’s temperature is increasing, we would predict an increase in biodiversity (1,2). A megalomaniac, on the other hand, having found power in climate change activism, would instead be incentivized to bolster the claim that humans are warming the climate via elevated CO2 and that this is going to be a disaster (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10). The point being, not all megalomaniacs on Mount Piety are the same. Some are expert at creating the illusion of knowledge while really only accruing information; and power depends on this confusion.

The result of this Dunning-Kruger-Power effect is a system run by people atop Mount Piety. Anyone driven by power would be unlikely to have descended into the Valley of Vulnerability, and any erudite who made it to the Humble Plateau would be perceived as less competent than those on Mount Piety anyways. It is not to say there are no powerful individuals not living on Mount Piety, but they represent a threat to the powerful ruling class — a Humble Plateau individual can knock someone off Mount Piety, or at least expose that someone is on Mount Piety. But how?

An Erudite and a Megalomaniac Walk into a Bar

What all this comes down to is, we need a way to tell apart the erudite from the megalomaniac for the purpose of exposing the latter. There is a very simple trick to do this, but it requires a touch of erudition of your own. The way to tell an erudite from a megalomaniac is to present them with a piece of knowledge that would have been acquired after descending Mount Piety. For example, any number of the references I provided above for knowledge an erudite might discover when researching atmospheric CO2 will do.

An erudite will be familiar with this knowledge, and will have already worked it into their cognitive framework. A megalomaniac will lash out because you just lobbed a rock at a glass castle. The stark disparity in how an erudite and a megalomaniac respond to post-piety knowledge is how to tell them apart. The erudite will be calm, patient, thoughtful, and considerate. The megalomaniac hostile, reactive, offended, and defensive.

What all of this means is that the Dunning-Kruger effect is not about knowledge at all. It is about power. And, as it turns out, knowledge is not power, power is power.

As for you? Be an erudite. The world has enough megalomaniacs as it is.

I just came upon your substack today and have read a large portion of your articles. There is a lot of valuable material in them. I found numerous insights and well-presented arguments.

Nevertheless, your anti-religious bias is quite apparent, and I would hazard to guess that you do not have much detailed knowledge of religion, in general or in particular. It seems to me that your mental picture of religion is quite cartoon-like, formed from stereotypes, extremes, and bad examples.

All of which leads me to conclude that you are firmly located upon Mount Piety with regards to religion. This is an irony and a terrible blind spot for someone who writes about how other people's confidence in speaking out about a topic vastly exceeds their knowledge on that topic.

Lastly, intellectual exploration into sociological topics should be taken in order to understand, rather than to mock those less erudite or intellectual than oneself, or to signal one's own superiority to them. Otherwise, it's merely a parade.

Brilliant summary of Dunning-Kruger !!